In advance of the forthcoming Wheeler Centre panel discussion No Place Like Home: Australia’s Housing Affordability Crisis, host Priya Kunjan has undertaken several interviews with individuals with lived/living experience of housing insecurity in Melbourne. This is the first interview in the two-part series. Find out more about this forthcoming event at The Wheeler Centre here.

Laura* is a cis queer woman in their late twenties. They are a community organiser and private renter, and are currently the court appointed guardian of a teenage child in community detention. Community detention, introduced in Australia in 2005 via an amendment to the Migration Act 1958 (Cth), allows the federal Minister for Immigration to make determinations about the residence of people in immigration detention within the community. While community detention is often framed as a more just alternative to detaining people seeking asylum in closed facilities, these determinations also work to transform the home-spaces of detainees into internal satellites of Australia’s carceral border regime.

Laura met me in a public park that they frequent as a space to relax and debrief about their various caring and organising responsibilities. We spoke outside in an effort to minimise Covid-19 risk.

Priya: I thought we could ground the discussion by talking about what the terms housing stress or housing security, housing insecurity mean to you, or what comes to mind when you hear those terms.

Laura: Housing stress, I feel, is around if you’re struggling to make rent, or if you’re consistently – or not necessarily consistently, but you can’t really get settled somewhere. Because things happen that affect it, like the rent goes up, or the landlord’s constantly saying, ‘I’m going to sell the property,’ or whatever. So basically, I guess, not owning your own home, and also having bad luck. I mean, at the moment it isn’t even really about bad luck. It’s, like, rental crisis.

Yeah, actually, I’m interested in what sits between the intersection of bad luck and rental crisis, because it is that kind of question of structural forces, and then your agency in navigating them. Can you tell me a bit about your own experiences of housing stress?

I guess, in different ways, I’ve had different kinds of housing stuff going on. I’m very fortunate because I can kind of work the system – I have a clear rental history that I maintain mostly just through lies. And I know how to write, I can write well ‘cause I’ve had an education and stuff. I can present what they want to know, the real estate agencies and landlords. So, in that way, it’s been good because I’ve been able to access housing most of the time, but it’s also just this constant, like, double life just to do that, when there’s no real reason … Because I’ve just been on Centrelink my whole adult life, so if I was honest about anything in my life, I would never get housing ever. I’m just constantly rearranging stuff, or constantly hiding housemates, or hiding myself or, you know, lying and living in fear of the landlord showing up or noticing something, so I guess that’s pretty stressful. And then more recently, now, it’s a lot around the ‘actually being able to afford the housing’ because I have a young person living with me, and I needed to get somewhere much nicer than I would need for myself. Like, I’m happy to just squat or live in a, you know, derro share house kind of vibes with nice people. But yes, you need somewhere fancy.

I suspect that just means a decent house.

Yeah, it doesn’t have anything actively dangerous or wrong with it. I’m used to living in places that maybe don’t have running water, or gas, or electricity. And then the share houses are like, half a step up from that? If I’m actually paying rent somewhere? Sometimes not even, sometimes the squats I’ve been in have been in better condition than the houses. Not often, but definitely sometimes. But then you don’t get the stability. But yeah, now that I’m actually [renting] through a real estate, which I don’t normally do, there’s inspections all the time, and it compounds the inspections we have from Home Affairs and DFFH and stuff. It’s just weird and constantly, like, ‘Okay, what things do I take down for this thing? What things do I move around? Do we have a kid? No.’ ‘Cause you’re not allowed kids anyway, so yeah. Not nice, I guess.

Effectively, my house is, well, it’s not effectively, it actually is something called – Do you know what community detention is?

Yeah.

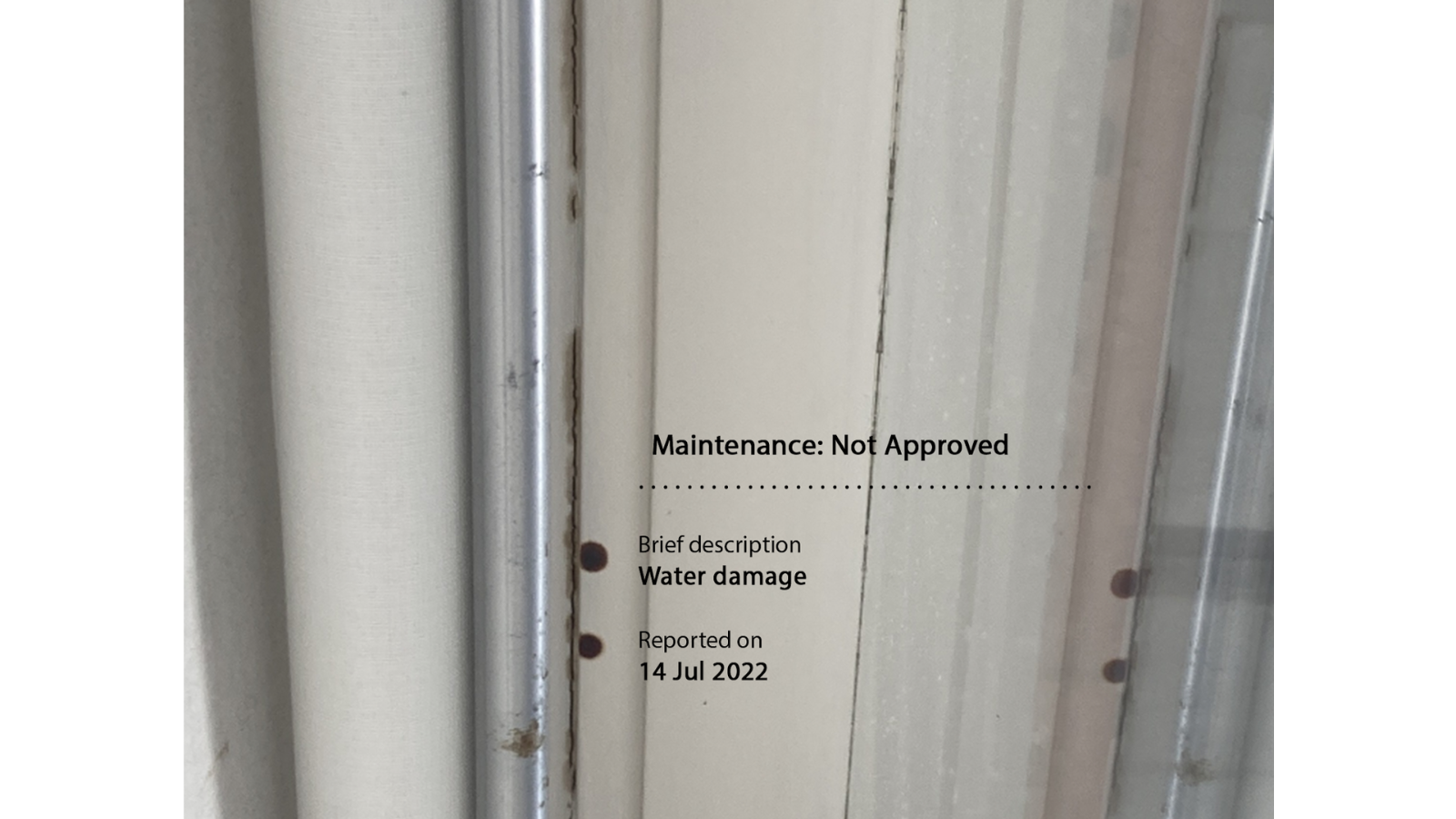

Yeah. It’s because the child that I’m looking after is in community detention. So that means we have to, it has to be, even though it’s not owned by Home Affairs or anything like that, they have to come over and make sure that we’re not having visitors and there’s no alcohol and no one sleeps over. And that the child I’m looking after is there, and blah, blah, blah. So they’re there and they do inspect stuff and sit around and just make everyone extremely uncomfortable and feel surveilled. And then child protection does basically the same thing. And they report to each other. And then immigration could come, but they haven’t yet, but they could, they can come at any time. Any of them can come at any time. But so far, they give me warning because there’s no reason for them to just rock up. But they could. So there’s them, and then there’s the real estate agent and landlord. And then I guess extensions of them, which to me is anyone that they send to the house. Because I don’t feel that they would be that far removed. So they kind of feel like inspections when it’s maintenance and stuff.

And on the real estate’s side, there’s not meant to be a young person in the house.

No.

But then on the Home Affairs side, it’s specifically a place where a young person is in community detention.

Yes, yeah. She’s not allowed to be anywhere else.

There’s so many specific considerations that you have to navigate while trying to find somewhere to live. How does that make you feel about your house – does where you live feel like home to you?

It does a bit. Yeah, my room does. The house, I think, me and the young person, we’ve talked a lot about how important it is that people aren’t coming into our rooms. And I think that also contributes to feeling like that’s my home area. Unfortunately, sometimes they have forced their way into her room. Not physically forced, just by intimidation and being ignorant, which I’ve put a stop to, obviously, and complained against that worker, but yeah. At the time, I wasn’t expecting them to just barge in there after telling them multiple times that that would be bad. So I think that affects whether we feel like it’s home. And then also moving less frequently, I feel like because we stayed at the last place for a year and that really started to feel like home. So I think the longer you’re somewhere, that really affects that. Which a lot of people don’t get to feel ever, because they’re just constantly jumping around. But that’s something I really want for her to feel, because she’s had to move heaps and just gets told where to live. So I’ve tried to keep her as stable as possible. Because that’s kind of what home means to me. It’s just the same place.

And I guess it’s compounded by the fact that her sense of being able to be at home has been so fundamentally compromised.

Yeah. And just violated constantly. I feel like I push back all the time against who’s coming to property when, and how often, and just put up as many barriers as I can. So for example, I’ll ask them to meet us at the park, and they’ve gotten really upset about that. And then I’ve contacted other people, like doctors, therapists and whoever I can to be like, ‘No, you have to do it.’ So that they’re one time on, one time off, that kind of thing. But yeah, it’s an ongoing thing. And then if the worker changes, then it’s like, they don’t pass on any notes.

If people with more power to change things, or who have sway could just have an open mind to the huge variety of different experiences, and not think that people are just dole-bludgers or whatever – I don’t know what the middle class think. That sort of stuff just isn’t very helpful, because it kind of narrows your focus a bit to at worst just being punitive, and at best, like, charity? People might not be so different from you that you need to be deciding what’s best for them, whether they need that level of support, if you can call it support. And with that in mind, trusting a little bit more that maybe groups, activists and people that also might seem different from you might have a better idea of how to do things than some huge NGO that hasn’t historically – like, there’s been no change. Just to look a little bit further outside the box, and trust people that are a little bit closer to the situations to manage stuff better. Because I just see a lot of huge grants going to places where I’m like, if we had that money in the housing group that I’m in, we would just do so much more with it. And I think that’s true for most of the Naarm left. But yeah, they don’t usually get that level of trust to change things.

*Name changed to protect privacy.

Related Posts

Read

What's on in July: Resident Organisation Round Up

3 Jul 2024

Read

No Place Like Home: What housing insecurity really feels like - Part #2

17 Jun 2024

Read

What's on in June: Resident Organisation Round Up

4 Jun 2024

Read

Read an excerpt from The Almighty Sometimes

30 Apr 2024

Read

What's on in May: Resident Organisation Round Up

29 Apr 2024

Read

Anne-Marie Te Whiu Receives The Next Chapter Alumni Poetry Fellowship

2 Apr 2024

Share this content