In advance of the forthcoming Wheeler Centre panel discussion No Place Like Home: Australia’s Housing Affordability Crisis, host Priya Kunjan has undertaken several interviews with individuals with lived/living experience of housing insecurity in Melbourne. This is the second interview in the two-part series (read Part One here). Find out more about this forthcoming event at The Wheeler Centre here.

Francesca* is a trans South East Asian person in their mid twenties. They are a community organiser living with the ongoing effects of colonial debility and kinship disconnection. The term debility is used here in the sense invoked by queer theorist Jasbir K. Puar, who uses it to identify the endemic production of slow death and disposability of some bodies within a system of colonial, racial capital. Francesca emphasised the importance of using debility rather than disability to frame the way that some of our capacities are shaped and circumscribed under neoliberal logics of agency, choice and personal responsibility as a core feature of their housing experience.

Francesca and I spoke over video-call after negotiating how best to create an interview space respectful of access requirements and COVID-19 safety. We took breaks during the interview and collaborated extensively throughout the editing process to ensure that the nuances of their experiences of unhoming and debility were appropriately reflected in the ranscript below.

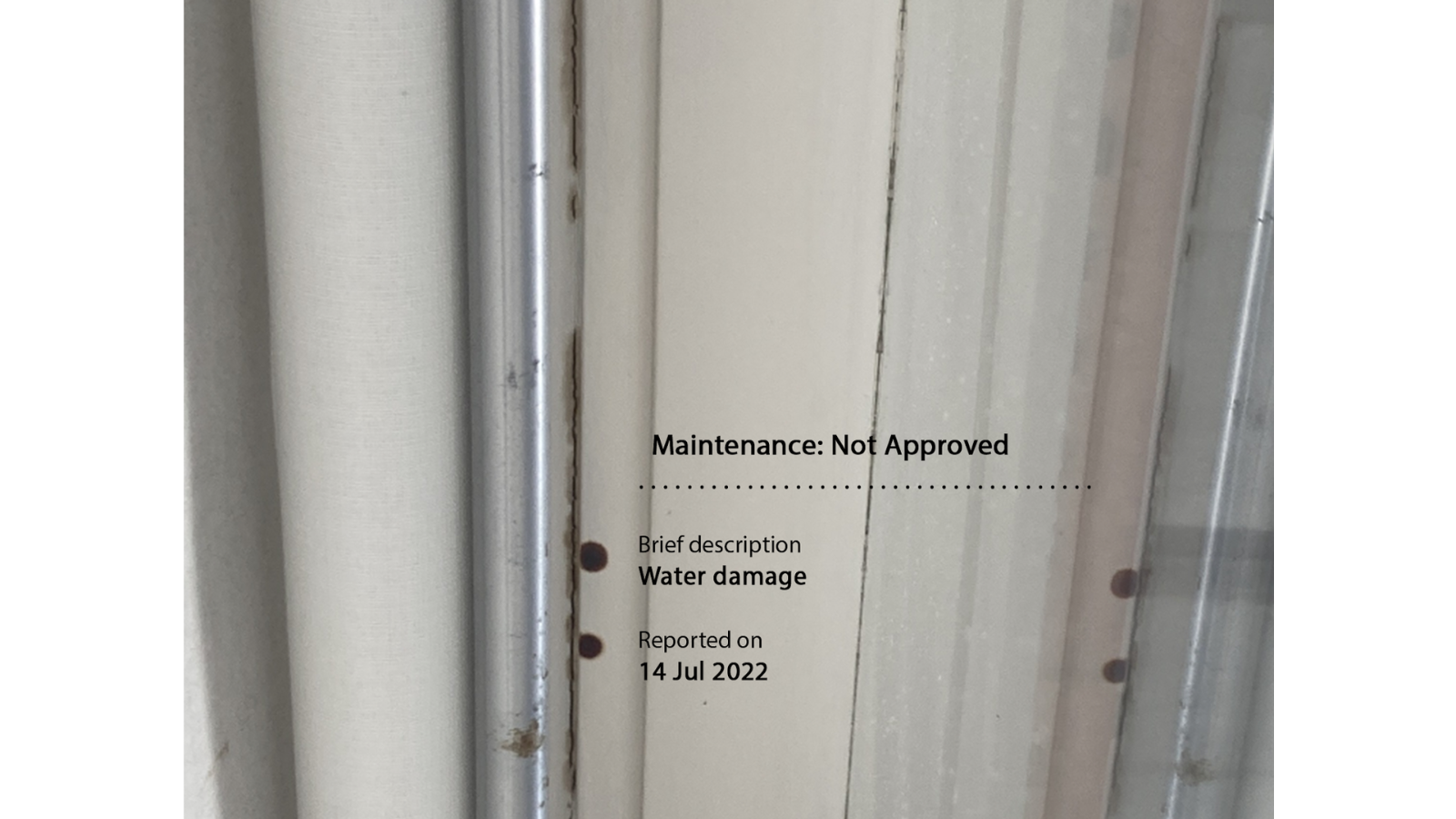

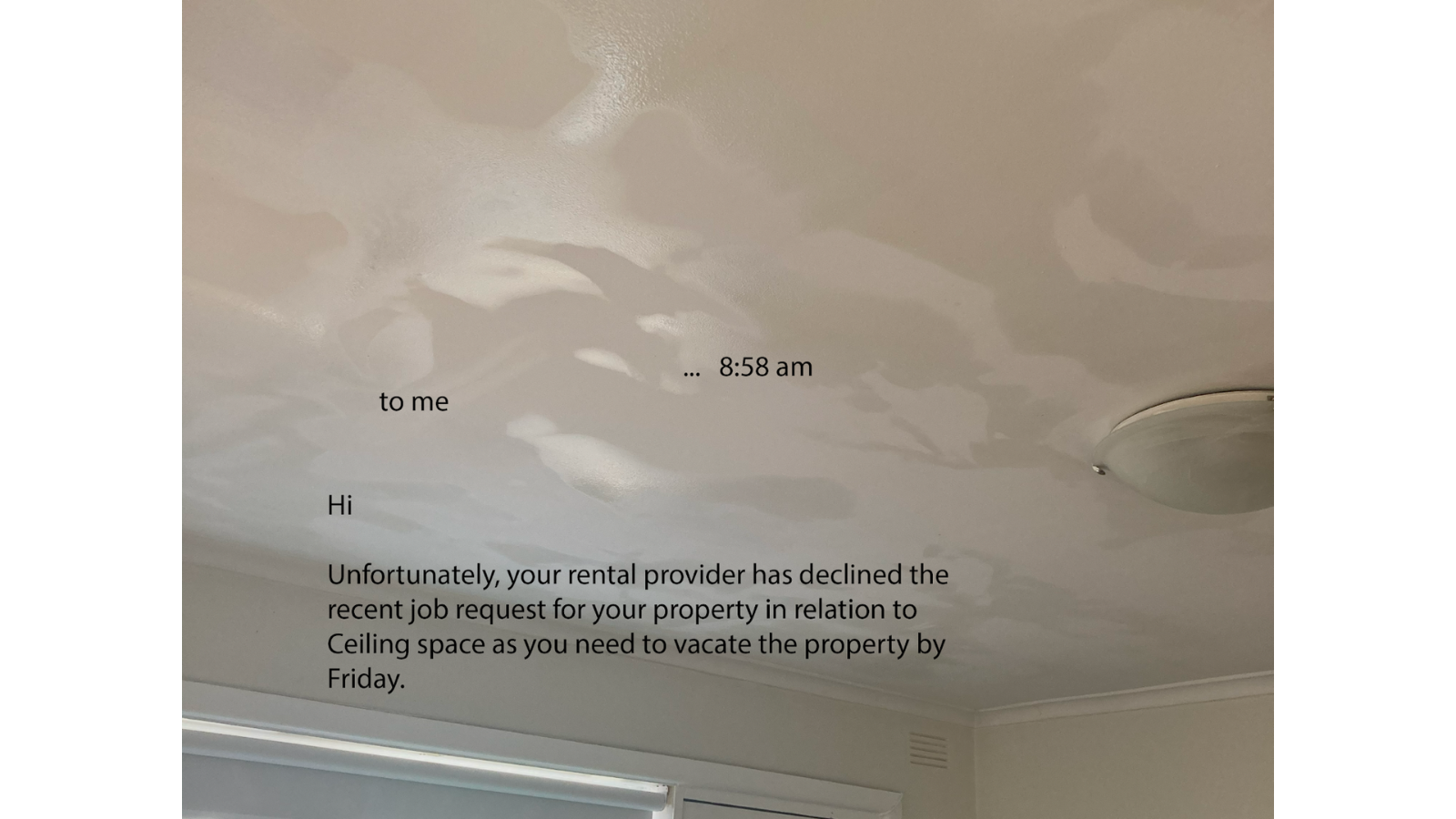

The images interspersed throughout this interview are composites I made with snippets of correspondence from one of Francesca’s previous property managers and photographs of significant water damage in the property taken by Francesca.

Priya: Can you tell me a bit about where you’re speaking to me from?

Interviewee: I’m speaking to you from inside my rental in the Inner West. This is the first stable housing, though there’s a bunch of complications in that, that I’ve been in… in several years? I’ve experienced houselessness basically since I was a teenager, because I ran away from home due to domestic violence. And I’m kind of surprised that now, in my mid-20s, houselessness seems so permanent as a part of my life. Also, I’m in this housing off the back of a lot of experimentation with how to… I don’t know, just not be in a situation where I’m renting from a landlord I don’t know and an agent I’ve got bureaucratic degrees of separation from. I’ve found that in the past, that kind of setup has allowed a lot of mistreatment. Not to say that if you actually know your landlord it will reduce any of that mistreatment. But I’ve been in housing ever since moving to Naarm in 2019 that I’ve experienced a lot of landlord malpractice in, allowing structural mould problems to go unchecked for example, and that’s impacted the health of myself and my housemates, who were also multiply marginalised, whether they were chronically ill, or First Nations or people of colour, or queer and trans people.

When you hear the terms ‘housing stress’, ‘housing security’, ‘housing insecurity’, do those resonate with you?

Yes, they do in some ways… But that language feels distinctly from a different place than the language I’ve been around for most of my life. I inhabit an unusual class position in that my parents are both first generation migrants who escaped their ancestral lands because of war and its ongoing effects, and then became middle class settlers here. Because I was dealing with domestic violence from them, which included having my clothing destroyed or even experiencing inconsistent access to food and things like that, the effects of which were socially visible to my peers, my position was fraught. But I have this liquidity in the sense that I went to a private school in my final years of high school. And so when I finally managed to run away from home – which also involved kind of cutting my lineage of (fraught) financial stability, right? – I did so by being taken in by fellow students, who empathised with me, and who were rich. I think for a lot of folks who are in more of a static or lower-class position, especially if separated from or without extended family, it’s very much like, welfare state, domestic violence shelters, which are obviously always really full, and yeah, chaotic. And from a young age, I bypassed that because of my privileges. Which shaped my experience in a different way.

I feel maybe a bit alienated from terms used within mainstream political discussions of houselessness because of the ways that I’ve been strategising to survive through til now… I’m trying to locate that I haven’t gone through a lot of the kind of government and state sponsored ways of avoiding my houselessness? And that was really important to me, even though I wasn’t as conscious of it at the time, in terms of my own dignity. Which is a funny term and in and of itself, associated with wealth and access. But yeah, it’s also been negative in the sense that it’s put me into situations where I’m in exceedingly close contact or dependent on people in my community, and how that closeness allows more… I don’t know how to say the word… violent, right now, but yeah, more violent dynamics. It leaves you susceptible to abuses of power from people you might never have a bad encounter with otherwise. And I think these dynamics are even more rampant when you’re forced to rely on nuclear family, and normative structures of wealth, which are built to enable systemic violences and support their intimate manifestations. And now, I’m even thinking about the wider conversation that’s being had right now about domestic violence. But anyways, what I’m also trying to say here is that these encounters I’ve had… they’re a consequence of the kind of social, I don’t know… Priya, can you pull a word for me? Like, the social…

Context? Or, like, a systemic kind of thing?

So, whatever the hell is going on in policy, right? It’s creating the conditions where even within my own community in spaces that are more, I guess, refuge-like… It’s like, even when you go out into community, and you try experimental projects there, we’re all under the pump and being fucked by these policies. And that that social condition creates the propensity to violence. And I think that somehow, I want to bring that into this conversation.

Yeah, that idea that we’re positioned to relate to each other in particular ways within a system of enforced scarcity, within a system of colonial racial capitalism, that then has an influence on how we can relate to each other. It doesn’t make it inevitable. But it certainly orients us in a particular way, so that it’s not as simple as saying that by virtue of being from the same community harm is impossible.

If I wasn’t seeking support in the community, the harm would be inevitable. Whether it would be relying on my parents, who I know would harm me… Also, I think, relying on state services… I’ve never met a single person in my life who hasn’t experienced the violence of state services and bureaucracy, and being pathologised and deemed deficient and being flattened, and not really being able to get the care that they need to survive, let alone be well.

In the aftermath of being taken in as a teenager by people around me, I was working several jobs. I was in high school at the same time. And there was always the threat that I would have to drop out. I was across living between my car when I had to work in the city, and this farm that I had moved to an hour out of the city, and then also moving between different people’s houses in the community I was in at the time, which was upper middle class, private school educated people and their families. And then after doing all of that work and saving up money, I did the classic thing and I started travelling. And I think travelling is, like, the antidote to when you fall through your community. I mean, there were a lot of social costs right after I ran away from home when rich people who were weird about homelessness started talking. And there was kind of this offer of, you know, if your community thinks you’re this weird poor person or whatever, you can choose the neoliberal dream of being self-sufficient and being on your own as refuge. I think going back to the state care side of things, I was on Centrelink and had social workers back then. And they were all really encouraging the idea of using this time to become independent and to become a good worker. And to use this aftermath of domestic violence to become more class mobile. Like, a lot of adults admired me. “You’re so young”, and like, “you ran away from domestic violence”, “you’ve got such a bright future ahead of you,” kind of vibe.

Yeah, this idea that houselessness becomes the springboard for you to engage in class mobility, but also, I guess, a form of assimilation.

And it’s definitely, like, I seemed middle class though at that point I had no money, and people relate to middle class domestic violence victims more than they relate to poor people. It was just a lot of ‘it can only go up from here’ logic that wanted me to live a certain life – predicated on getting me to believe in neoliberalism, in my parents as the source of the violence rather than the intimate violence as a manifestation of systemic violence, my abusers as bad and “the world” as good, etc. And I did. I believed in it and busted my ass so hard that I was put on antibiotics on repeat for almost an entire year, since I was always getting sick and never able to recover. But it’s not like I had any other choice. The belief was a side effect that made it easier.

When I started navigating the world as a 17 year old, with my savings, moving around, I was like, “Whoa, people don’t see me as homeless. They see me as a digital nomad.” [laugh] People don’t see me as un-familied or estranged. And I’m more free from socially un-valuable identity markers and the kind of treatment that I receive because of them, and I’m also less racialised. Parts of my identity, colonial privilege, were doing a lot of work to mean that I was being seen as more fascinating, more engrossing and had more potential. And I was being looked after by people, you know? Because when you’re travelling, even though you’re on these neocolonial pathways of motion, you have to look after each other because there’s no one else to look after you. And so I was housed, I was fed, and I didn’t have to spend much money on these things, if at all. Whereas when I was living within the settler state, it was like, it’s really fucking expensive to be poor. If you have the ability to be mobile, then yeah, free shit comes your way! [laugh]

I lived like that for quite a few years before I came here. And in the first years I spent here, people saw me as this young, well travelled and courageous person with a lot of social mobility. That was tiresome for me, and increasingly fraught and difficult for me to maintain the more time went on. I was treated way better in terms of housing because of this image. I made this joke to myself not long ago that I think I’ve lost the privilege of… for example, when people post on their Instagram story saying, ‘my beautiful friend who I love so much is seeking a house, please send options our way.’ And I realised, after a few years of being here, that I’m too disabled now to be considered anyone’s beautiful friend. [laugh] I lost a lot of the visibility that I needed in order to be able to find housing in the first instance after I got sick. And I also lost the kind of valuations, colonial valuations that people seek in allowing and permitting someone to be in their house, and to be their housemate.

You described how debility has affected your relationships with community but also impacted upon your relationship to housing, which has sort of changed over the past few years. Can you tell me maybe a little bit about that period of time [where] there was a period of hypermobility, and when that sort of changed?

The process of becoming debilitated… I mean, there are long origins of that, that run through families and cycles of intergenerational colonial violence. Obviously, being abused for my whole upbringing didn’t help my health, but I was healthful during my travels, you know. It was like, once I got off this continent, I was raking in 30,000 steps a day, working in photography and I think of it now like, “wow, I was a machine.”

Something that happened after the first couple of years of things being okay was the 2020 bushfires. I was living in a sharehouse at the time – it was the first sharehouse that I was permitted access to that seemed like it was long term. It had this really big garden. It was all queer white people who had known each other for quite a while, and were established in this city. And so it felt rare that I was permitted into that space. And the more that time went on, the more it became obvious how conditional that belonging was. But I moved in, and there was black mould, and I wasn’t too concerned since I thought it could be removed. But then, when the bushfires were happening, and the air quality was – on the AQI app, like, purple zone. It’s bad for everyone, you know. I was like, oh, I can’t spend most of my time outside like usual, I’m getting this hardcore mould exposure all the time, and it’s a pitfall that this house has a bunch of big cracks in it and that it’s so permeable. But also, colonial style architecture is not designed to be permeable. It holds dampness in these really shit ways. I think I was yearning back then, thinking about houses in the archipelago that are way better with breathability.

I said to my housemates, “Hey, can we please keep the doors and windows shut? I’m concerned about all this smoke getting in.” And I remember my housemate at the time was smoking a cigarette on the back porch. She was like, “Yeah, I’ve been to Nepal… The air’s shit there.” And it’s just shocking. She said it like it made her immune. I was like… exposure is cumulative! It was a clear example for me of white entitlement and disconnect from Country, and believing that you are separate from or above what’s happening to Country, even if your lifestyle, in a way, is producing the type of fire. So I was like, “okay, whatever,” and shut the door. My other housemates were way more nice about it. I feel like I need to use this word nice in a specific way. White people really value being nice. They all seemed amenable to my request, but they didn’t do what I asked. Eventually, I developed asthma that I had never had before. And I couldn’t breathe. And I was calling up NURSE-ON-CALL, like, “I can’t breathe, but I don’t know whether I’m just-” you know. I think when a healthy person first gets sick, it’s like, “am I making this up? Is this real or is this not?” And they’re like, “No, of course you’re experiencing that!” And it’s something that I see come up in disability justice communities worldwide, where they’re the only ones that will tell people “hey, yeah, you actually can’t breathe, this is real.”

The bushfires got really intense. And then coronavirus started spreading around that time. And what I experienced was this second round of a flattening of socially enforced distances, travel being the first, which meant that people were relating with a kinship I was used to giving and not receiving, because it was like, we’re all trapped, we gotta rely on each other. And I was really shocked at that time because when Coronavirus started… before the lockdowns got too real, all four of my housemates just went back to their family’s home or second home. I was like, “What the fuck?!” [laugh] “I’ve got nowhere to go.” And I think their access to other homes made me realise why they’d related to this home with such nonchalance and why I was such a disruption to that setup. So I was left with this house, which as I said, was difficult to gain access to in the first place. It was big, it was relatively affordable when split between five, it was inner north and it had this big garden space with a lot of potential. And this is gonna be the sad joke of the whole story, but I felt this structurally busted house was a great opportunity. I thought, “Wow, maybe I can fix this house up, have a full non-white share house of people who are actually in community and organising, maybe I can actually use this space to distribute food, and to work on collective projects that I always wanted to.” And it was really, extremely hard.

Eventually, I got the sharehouse together. By which time I was starting to get sick in other ways. And this was connected to the black mould, which was structural, and couldn’t be fixed by the “landlord special” of continuously painting over it, as they’d done several times. And structural mould and sick building syndrome, it’s actually a really fucking big problem, that I don’t think is accurately represented in numbers, because of all these old shonky Victorian terrace houses that wealthy investors love to keep and rent as sharehouses, cost millions and would cost millions to actually renovate to liveable standards. And a lot of people don’t necessarily get sick because of it, which I believe is also in part connected to having spaces of retreat, but a percentage of people do.

At the time I weighed the risks and thought, “I barely know anyone sharehousing who lives without it, it must be how it is.” Which was more my coping mechanism for the fact that I couldn’t find anywhere else to live. And yeah, we were growing and distributing food, and gathering, and organising a lot from this place. There was a lot of joy. And there was a lot of struggle. I won’t say more than that.

But growing increasingly unwell was linked to this exposure to fire and the dynamics related to it, which set off inflammatory processes, followed by all the ways that I sought care and sought ways of making sanctuary that didn’t work out for similar reasons. And so there was this compounding, and it would be difficult to honour how all these instances of structural racism worked because that would be another interview, but by this point, I had to rely on my friends more because the house was making me sick, and the medical system wasn’t helping me, and kept telling me I had anxiety, which I’m sure is an experience a lot of queers and racialised people can relate to. Which four years on has turned out to be over ten diagnoses of autoimmune diseases and their comorbidities that the medical system is notoriously bad at taking seriously and identifying, mind you. So I sometimes had to stay over at people’s houses if the smoke was really bad, or the structural damp was too much, or if there were thunderstorm asthma warnings, things like that.

And this group I was building relationships with, some of them I’d only known for a few months. It was casual to rely on each other that much when I was travelling but it’s not so cute when you’re in the city. The more time went on, the more it really became apparent like, “oh, shit, you have nowhere to go.” Coronavirus did enforce periods where we all had nowhere to go. But between every lockdown, people would retreat. And I remember I found it profoundly bizarre, because I thought I was in a relatively good position in this sharehouse where we could build queer fam ways, and I desperately needed that for most of my life. But other people didn’t.

There are all of these different compounding factors that lead to you moving from this state of healthfulness to debility that are also profoundly related to the people around you, the people that you’re, you know, forming a household or forming communities with, and this idea of shifting into a very different position in relation to what it means to be mobile in a housing sense, that then creates this looping effect, where it’s not just like, “oh, you got sick and then housing got hard.”

And I can’t convey like, the thing that’s really painful about it is that it was so slow. And by virtue of that slowness, [it was] illegible or unrecognisable along settler colonial lines. In the ‘slow violence’ politicised term way, which again, to get into those dynamics properly would be another interview… Honestly, a huge part of it is – and I think it’s very obvious in the way that coronavirus is treated as “over” now – is that middle class people desperately need their access to cafes, restaurants, and spaces of gathering under capitalism. And capitalism needs them to need that. Those spaces kept me well. When I first moved out, and I wasn’t as emplaced… it became very important for me, especially as part of the solo travel dream I was sold, to frequent those spaces and find connection through consumption, in the absence of sustained connection to ancestral place, culture and kin. The only spaces of connection, especially in cities, were cafes, libraries, restaurants, galleries and universities. Capital-mediated spaces. And I also want to extend that to say that the relationalities formed in these spaces are mediated by capital too. And what does that mean if these are the only places you encounter people? What does that mean if the relations you sustain your life with are built on these terms? Because I think the part I’ll probably get to by the end of this is that we relate to each other in these weird micro-entrepreneurial ways, where people will invest in someone who seems like they’re up and coming and desirable, right? They will produce “love” and “care” along those lines. And then it’s like, “oh, I feel like a stock.” People were like, “oh, she’s going down, we’re divesting.” [laugh] Resources were freely gifted to me while I didn’t need them, especially when I was at the peak of being recognised for my organising work, and suddenly became unavailable the more I needed them.

It was a long walk for me to this profoundly alienating place. Even back then, it was like, I’m engaging with these doctors and these bureaucrats by myself, constantly, with no witness, with no one to advocate for me, and they’re all treating me like my sickness, my embodied understanding of it, and the colonial forces at play here aren’t real because they can’t fit them into their framework and have no need to shift these conditions. Coloniality can’t recognise itself as a driver of debility. And by the time lockdowns had lifted I had become so sick, largely due to medical neglect, that I couldn’t return to my ancestral lands, so I’ve been forced to keep investing in this system to try and get better. And I’m spending increasing time and money and energy on these people, and also the people around me are un-seeing me in a different way. All these interactions are part of a vacuum of disposability.

*Name changed to protect privacy.

Related Posts

Read

What's on in July: Resident Organisation Round Up

3 Jul 2024

Read

What's on in June: Resident Organisation Round Up

4 Jun 2024

Read

No Place Like Home: What housing insecurity really feels like - Part #1

3 Jun 2024

Read

Read an excerpt from The Almighty Sometimes

30 Apr 2024

Read

What's on in May: Resident Organisation Round Up

29 Apr 2024

Read

Anne-Marie Te Whiu Receives The Next Chapter Alumni Poetry Fellowship

2 Apr 2024

Share this content